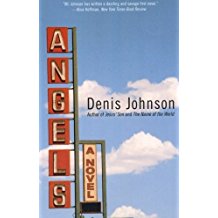

Photo: Detail of cover of Resuscitation of a Hanged Man

By Kevin Rabalais

At the start of most years, soon after I finish my annual New Year’s Day reading of The Great Gatsby, I often find myself thinking about Denis Johnson. I can’t explain it. All I know is that, for whatever reason, with the turn of each calendar year, I want to inhabit the world of Johnson’s voice. It’s not that, as Jonathan Franzen writes, “The God I want to believe in has a voice and a sense of humor like Denis Johnson’s.” There’s something else going on, something humane, not to mention seductive about Johnson’s world.

And so I often begin the year by re-reading one of his novels. What inevitably turns into a marathon might commence with The Stars at Noon, narrated by an American woman on the run in Nicaragua in 1984. Or it might begin with the reportage collected in Seek. The first sentences of the opening piece, “The Civil War in Hell,” get me every time:

"It’s late September and the Liberian civil war has been stalled, at its very climax, for nearly three weeks. The various factions simmer under heavy West African clouds. Charles Taylor and his rebels are over here; they control most of the country and the northern part of the capital, Monrovia—the part were the radio station is, and many nights Taylor harangues his corner of the universe with speeches about who he’s killed and who he’s going to kill, expectorating figures with a casual generosity that gets him known as a liar, referring to himself as 'the President of the nation' and to his archrival as 'the late Prince Johnson.' Meanwhile Prince Johnson, very much alive, holds most of the capital."

Before I know it, weeks have passed, and I haven’t even thought about reading anyone, anything, else. Once you enter Johnson’s world, it’s difficult to leave. He continually finds new ways to welcome and embrace you. Then he keeps on giving.

Consider another opening, this one from the wonderfully titled novel Resuscitation of a Hanged Man, about Lenny English, a drifter recovering from attempted suicide who finds work in Provincetown as a disk jockey/private detective.

"He came there in the off-season. So much was off. All bets were off. The last deal was off. His timing was off, or he wouldn’t have come here at this moment, and also every second arc lamp along the peninsular highway was switched off. He’d been through several states along the turnpikes, through weary tollgates and stained mechanical restaurants, and by now he felt as if he’d crossed a hostile foreign land to reach this fog with nobody in it, only yellow lights blinking and yellow signs wandering past the car’s windows silently."

I spent much of the past three months preparing for an on-stage interview at the Auckland Writers Festival with Johnson, who died on Wednesday, May 24. He cancelled his appearance several weeks before the festival, but it was a great pleasure—and often an education—to read and reread his books and prepare for the meeting. He didn’t give many interviews. This, along with my awareness that most of his fans can recite their favorite passages even while distracted, raised the stakes. Johnson saw poetry in decay. He found light and life in the lives of the downtrodden characters who populate his books. Among the many of my favorite passages is the scene in his story “Work” from Jesus’ Son, when the narrator reflects on everybody’s favorite bartender:

"Who should be pouring drinks there but a young woman whose name I can’t remember. But I remember the way she poured. It was like doubling your money. She wasn’t going to make her employers rich. Needless to say, she was revered among us. … The Vine had no jukebox, but a real stereo continually playing tunes of alcoholic self-pity and sentimental divorce. 'Nurse,' I sobbed. She poured doubles like an angel, right up to the lip of a cocktail glass, no measuring. 'You have a lovely pitching arm.' You had to go down to them like a hummingbird over a blossom."

I could go on, but I’d rather get back to reading the work that Johnson left behind—poetry, plays, stories, novels and reportage that heeds his own advice about writing:

“Write naked. That means to write what you would never say.

Write in blood. As if ink is so precious you can’t waste it.

Write in exile, as if you are never going to get home again, and you have to call back every detail.”