By Jennifer Levasseur

In uncertain times, many of us look to fiction for explanations, clarity, hope. While it might seem counterintuitive—how can the lives of fictional characters explain to us the reality that we’re living?—novels provide a slower and more complete reflection of life as we know it and, more importantly, life as we have not experienced it. But as a form, the novel often looks backward.

Placing aside those that display an uncanny prescience (such as Laurence Wright’s recent The End of October), we usually have to wait anywhere from two to ten years for the novel to catch up with what we’ve experienced and to provide us with a nuanced reckoning. For example, the most popular and lauded novels of September 11th began to appear on bookstore shelves in 2005. Authors (including Claire Messud, Jay McInerney, Jonathan Safran Foer, Chris Cleave, Ian McEwan, Don DeLillo, and Mohsin Hamid) worked that trauma from numerous angles through the rest of the decade and beyond. Somehow, few fiction writers ever took on the 1918 influenza they lived through. That will prove different for our own pandemic: already, literary agents and publishers recommend that aspiring writers move on; they’ve seen enough pandemic lit to last a lifetime.

With all this in mind, it’s important to remember that only so many plots, so many themes exist. While the details vary, most of what we seek is likely already out there in some version, lost to the ravages of fast-paced publishing, which demands instant results or the pulp pile. Or they were simply ahead of their time. They may even have been briefly lauded but are now inexplicably forgotten. Before the surge in books by and about LGBTQ individuals, for example, Dawn Powell published novels in the early 1930s that featured gay characters as a matter of course, with no comment, criticism, or celebration. Her work, however, fell into obscurity until Gore Vidal helped revive interest in the late 1980s.

There will always, we hope, be author revivals. There’s something tantalizing, sad, and ultimately triumphant about the author unappreciated at her time but celebrated long after death. It proves to us that we are more clever, more discerning than our forebears who held this or that genius in their midst and dismissed them. The lost author is almost a genre in itself.

The charming 2003 documentary Stone Reader follows an obsessive reader’s quest to discover what happened to another lost writer, Dow Mossman, author The Stones of Summer (1972). Mossman wrote a single novel and, upon its publication, the New York Times compared it favorably to early works by Bernard Malamud and Philip Roth. Another New York Times review summed up the novel’s achievement: “Fulfillment is perhaps the best word, fulfillment at the first stroke, which is also a frightening thing, for the author may remain forever awed by the force and witness of his first production.” Mossman never published another book and quickly fell out of print.

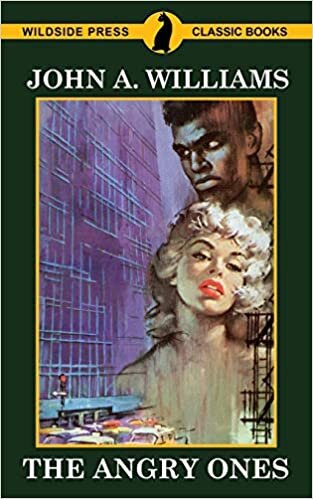

Memory is a funny, untrustworthy thing. My husband believed we discovered the under-appreciated writer John A. Williams through Stone Reader. He assured me that the filmmaker interviewed him about continuing to write in relative obscurity and with lackluster sales even though he’d won many awards and taught at a variety of universities. Not to be confused with the author of Stoner who was also named John Williams and escaped from literary purgatory through reissues by New York Review Books, John A. Williams (1925-2015) began publishing in the early 1960s and kept turning out novels, biographies, and articles for decades. In its notice of his death, NPR discusses Williams as “one of the most prolific writers most people have never heard of.” The New York Times referred to him as “chronically underrated.” Even today—after several American Book Awards, a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, laudatory reviews, and scandal—several of his novels remain out of print or are available only in electronic versions. (Try looking for a hardcover copy of The Man Who Cried I Am and you’ll be rewarded with a quote of about nine hundred dollars. Coffee House Press, however, keeps a couple of titles with handsome jackets in print.)

When we finally tracked down a used DVD of Stone Reader, we watched its two hours—filled with agents, writers, publishers, and readers singing the praises of William Gaddis, Ralph Ellison, and Joseph Heller—and waited for John A. Williams to appear. He never did.

This is all the more unfortunate because John A. Williams is exactly the writer we’ve been looking for in this moment. We obviously did not learn about him from Stone Reader, but somehow around the time that the documentary was released, we started picking up battered editions of Williams’s novels in secondhand stores, before dealers realized their potential worth: Captain Blackman; !Click Song; Sons of Darkness, Sons of Light; Jacob’s Ladder; Clifford’s Blues. We mentioned his name to readers. As had happened with Dawn Powell and the other John Williams, our fellow bibliophiles shook their heads, eager to join the club. Unlike with those other two writers, reissues of John A. Williams’s books were quieter and unlikely to be found on many bookstore shelves.

These days, I’ve been thinking of John A. Williams as a literary face of the Black Lives Matter movement. While he never wanted to be pigeonholed solely as a “Black writer”—mainly because he feared that only one or two writers of color could be taken seriously at any given time and Richard Wright and James Baldwin had already been chosen—each of his novels strives toward that simple and profound message: Black lives matter. They are rich, they are joyful, they contain vast pain, their histories are often untold or, when told, are not believed. His novels say: Look at these humans. See how they live. Enter their homes and understand what they love and what they don’t want to lose, what they fear they’ll never gain. John A. Williams never peddled comfort. He had no easy answers because none exist and he refused to pretend. If I write as though I know his mind, it’s because his books make the reader feel that way. They’re intimate, challenging, vulnerable. But never safe. He courted controversy with his 1970 biography of Martin Luther King Jr., The King God Didn’t Save, which focused on the Civil Rights leader’s shortcomings and questioned how much he actually did for the movement. This alone may be a reason the novels of Williams have failed to become part of the mainstream cannon.

Photograph by Kevin Rabalais.

Reading Williams’s novels, however, open a path into a worldview. James Baldwin described well in a 1979 interview how the creator always appears in his work. “Whatever you describe to another person is also a revelation of who you are and who you think you are,” he said. “You cannot describe anything without betraying your point of view, your aspirations, your fears, your hopes. Everything.”

Born in Jackson, Mississippi, Williams spent much of his life in New York. He published twelve novels, each one an education in content and in form. His first, published as The Angry Ones in 1960 (though he had titled it One for New York), describes racism in the North and interracial relationships. He wrote about jazz (Night Song, 1961); explored the life of a gay pianist from New Orleans living in Europe, snared by Nazis and shipped to Dachau (Clifford’s Blues, 1999); followed a single Black soldier through every American war, beginning with the Revolution and ending with Vietnam (Captain Blackman, 1972); and crafted a fictional biography of a Richard Wright-like novelist; he wrote so convincingly about a government conspiracy to relocate all citizens of African descent that many readers refused to believe the plot was fiction (The Man Who Cried I Am, 1967). The editor of Conversations with John A. Williams notes that his work has been likened to that of William Styron, John Cheever, Kurt Vonnegut, and Arthur Miller. In an interview in that collection, Williams refers to himself as a “writer-historian.”

I picked up Williams’s fifth novel, Sons of Darkness, Sons of Light (1969), last month when I remembered its premise, one written for our times despite its publication date. Its subtitle, “A Novel of Some Probability,” makes the setup somehow even sadder, more forlorn, and frankly, more terrifying. A white policeman kills an unarmed Black teenager and is held liable in no way. The city braces for protests, riots. Eugene Browning, a professor-turned-administrator of a local Civil Rights organization, is tasked with raising funds for the ever-struggling foundation, specifically to pay the inevitable bail for protestors. At the same time, Eugene tries to keep the peace between his daughter, who’s dating a white man, and his wife, who believes the relationship will come to no good, regardless of the man’s character. The futility of it all exhausts him.

Early in the novel, he thinks about how the days will proceed: “The telephone would ring constantly and the newsmen would barge in asking the same stupid questions and [his boss] would give them the same stupid answers. They would all play their roles.” He wonders what it would be like to foreswear nonviolence, to behave as the Old Testament prescribes: an eye for an eye.

After he’s made his decision, he seeks the help of his old building super, an Italian American who does “some of this and some of that.” Eugene tries to explain his motives. “I’m getting older and I haven’t made any waves, I haven’t made anything better,” he says. “It’s getting late. The place is going to pot in a thousand ways. I don’t want it to go to pot. I could like the place. The way it’s going now, the next time I see you, you’ll be at my throat or I’ll be at yours—”

Eugene, however, has no control of the force he unleashes. In his 1999 foreword to Sons of Darkness, Songs of Light, Richard Yarborough highlights the novel’s themes, which are “fueled by rage and hope in equal measure”: “the burden of empathy, the struggle for communication across racial, ethnic, gender, and generational lines, and the search for moral coherence.”

While Williams wrote this novel quickly and considered it a “potboiler”—complete with mafia hitmen and an Israeli enforcer with a questionable ethical code—its complexity and moral challenges make it much more than a thriller. As Williams moves the narrative among his characters’ consciousnesses, we learn how complicated, how conflicted their actions and emotions remain.

Photograph by Kevin Rabalais.

Sons of Darkness, Sons of Light is an uncomfortable book, one that exposes the fault lines in every subset of the community, in every human heart. A man can take a life and then nurture his child. He can hold great ideals and still feed ingrained biases. He can want peace and the comfort of his family while he encourages violence.

Novels never point toward the one true path; that is the purview of parables. The best they can do is offer to let us slip for a moment inside another hot, slick skin so we can live as someone else for a brief while, hoping that some of that DNA remains when we return to what we already know. John A. Williams is that kind of writer. If his words echo what you have experienced or feared, he gives voice to your worst and best impulses. If his characters at first seem foreign, by the end he makes you understand if not relate or agree. This isn’t to say that his work is pedantic—it is decidedly ambivalent in the true sense of the word—leaving the reader, gratefully, more troubled and thus more of a seeker than when she began.

Photograph by Kevin Rabalais.